The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is a crucial stabilizing ligament in the knee joint. Positioned centrally within the knee, it extends from the back of the tibia to the front of the femur. The PCL is notably thicker and stronger than the ACL and other knee ligaments. Its primary role is to prevent excessive backward movement of the tibia, thereby ensuring knee stability during activities involving rotational movements such as twisting, turning, or side-stepping. Additionally, the PCL plays a vital role in providing neurological feedback regarding limb orientation in space, which is essential for normal joint function during daily activities, occupational tasks, and sports.

Injuries to the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) are less common compared to anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries due to its thickness and strength. However, when they occur, they often result from significant forces. Motor vehicle accidents can lead to PCL injuries, particularly when a bent knee strikes the dashboard or in cases of falls onto a bent knee from a motorbike, causing the tibia to move backward forcefully. In contact sports like football and rugby, athletes may suffer PCL tears when falling on a bent knee with the foot pointed down, or from tackles that bend the knee during impact. Additionally, twisting movements or hyperextension of the knee, as well as simple missteps causing falls with the tibia striking against the edge of a step, can also result in PCL injury.

Meniscal injuries can affect either the outer (lateral) meniscus or inner (medial) meniscus, or both. Cartilage injuries may involve the articular cartilage lining the femur, tibia, or patella, ranging from minor flaps to major defects. Ligament injuries, such as those to the medial collateral (MCL), lateral collateral (LCL), or anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), are also possible. Additionally, fractures may occur in the tibia, femur, or patella.

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is a key stabilizing structure within the knee joint. Positioned centrally, it spans from the rear of the tibia to the front of the femur. Notably stronger and thicker than the ACL and other knee ligaments, the PCL plays a vital role in preventing excessive backward movement of the tibia. It contributes to maintaining knee stability during rotational movements, such as twisting, turning, and side-stepping activities. Additionally, the PCL serves an essential function in providing neurological feedback concerning limb orientation in space. This feedback is crucial for normal joint function during daily activities, occupational tasks, and sports.

Typical symptoms of an acute posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury include pain accompanied by swelling that develops steadily and rapidly after the injury. This swelling can lead to knee stiffness and may cause a limp, making walking difficult. The affected knee may feel unstable, as if it could "give out." In cases where there are no associated injuries to other parts of the knee, symptoms of a PCL injury may be so mild that the patient may not initially notice any issues with their knee. However, over time, the pain may worsen, and the knee may feel increasingly unstable. Activities such as kneeling or climbing stairs may become challenging. If other parts of the patient's knee are also injured, their signs and symptoms are likely to be more severe.

PCL injury is diagnosed through a combination of the patient's injury history, symptoms, comprehensive clinical examination, and diagnostic investigations such as X-rays and MRI of the knee. Special tests for PCL involve confirming excessive backward movement of the tibia over the femur, known as posterior sagging. While a torn PCL is not visible on X-rays, they may reveal posterior sagging of the tibia and any fractures of the upper tibia, such as avulsion fractures, where the PCL is normally attached. MRI scans of the knee are particularly useful as they can clearly visualize a posterior cruciate ligament tear and identify any accompanying injuries to other knee ligaments or cartilage. Additionally, MRI scans can detect bony bruises and fractures that may not be apparent on X-rays alone.

PCL injuries are typically classified into three grades: Grade I (Mild) involves microscopic tears or sprains in the ligament, causing minimal instability. Grade II (Moderate) indicates a partial tear of the PCL, resulting in some instability, with occasional giving out of the knee during activities. Grade III (Severe) signifies a complete tear or detachment of the PCL from its normal attachment point on the bone, leading to significant instability. Grade III injuries often occur alongside other knee injuries due to the high force required to cause them, such as ACL or collateral ligament sprains. The most common types of PCL injuries are Grades I and II, involving small sprains or partial tears. Treatment decisions are guided by the grade of PCL injury and the patient's symptoms.

Not all PCL injuries necessitate surgical intervention. Surgery may be avoided if the tear is minor (Grade I or II) and can heal through rest and rehabilitation, or if the PCL tear is chronic but symptom-free. For individuals with less active lifestyles or occupations not requiring significant knee stability, surgery may not be essential. Those willing to adapt their activities, substituting with low-impact exercises like cycling or swimming, may also opt out of surgery. Commitment to a rehabilitation program aimed at stabilizing the knee and strengthening leg muscles, even with some residual instability, can mitigate future injury risks. Conversely, for those lacking motivation for the rigorous post-surgery rehabilitation process, conservative management may be preferred.

Conservative treatment is often the initial approach for PCL injuries across all grades. It can be especially effective for Grade I or Grade II injuries. This treatment regimen typically involves a combination of rest from strenuous activities, application of ice packs to reduce swelling and pain, and the use of anti-inflammatory medications to manage discomfort and inflammation. Additionally, physiotherapy plays a crucial role in strengthening the muscles surrounding the knee, particularly the quadriceps, which can compensate for the PCL's stability functions. Specialized exercises may also be incorporated to enhance balance and proprioception. Functional knee braces are often prescribed to provide support and stability to the knee joint during the healing process, while also facilitating controlled motion exercises and promoting knee proprioception. Placing a pillow under the calf can further assist in preventing posterior sagging of the tibia as the PCL injury heals.

PCL reconstruction is typically recommended in several scenarios. Complete tears of the PCL, particularly Grade III injuries, or partial tears resulting in significant knee instability often necessitate surgical intervention. Concurrent injuries to other knee structures, such as the articular cartilage, meniscus, ligaments, or fractures, may also warrant PCL reconstruction. Additionally, displaced avulsion fractures of the upper tibia (PCL avulsion fractures) often require surgical correction. Individuals with high levels of activity in sports or occupations requiring knee strength and stability may opt for reconstruction to restore pre-injury function. Commitment to a thorough rehabilitation program post-surgery is essential for successful outcomes. Moreover, chronic PCL deficiency impacting daily activities and quality of life may prompt consideration for reconstruction. In cases where previous rehabilitation efforts have failed to achieve desired knee stability, surgical intervention may be necessary to address persistent instability.

PCL surgery serves two main purposes: Reconstruction for a torn PCL and Fracture fixation for a PCL avulsion fracture. In cases where the PCL is completely torn or there is an avulsed upper tibial fracture with attached PCL, abnormal mobility of the tibia during normal activities and sports can lead to continued instability, pain, swelling, and a compromised ability to lead an active lifestyle. Neglected or improperly treated injuries of this nature can result in secondary damage to the joint cartilage and meniscal tissues, potentially leading to early-onset knee arthritis. PCL surgery is recommended to restore or nearly restore normal knee stability, regain pre-injury function, prevent loss of function in the knee, reduce the risk of injuries to other knee structures, and deter premature knee degeneration. Ultimately, PCL surgery aims to enable individuals to lead an active lifestyle while minimizing the long-term consequences of their injury.

PCL reconstruction is a surgical intervention aimed at restoring the stabilizing function of the posterior cruciate ligament. This procedure involves removing the damaged PCL remnants and replacing them with a soft tissue graft. Various graft options are available for PCL reconstruction, with the most common techniques utilizing hamstring tendons (semitendinosus and gracilis tendons), Peroneous tendons or a BTB (bone tendon bone) graft. The BTB graft consists of a bony plug from the patella at the top, a strip of patellar tendon tissue in the middle, and another bony plug from the upper tibia at the lower end. PCL reconstruction surgery is typically performed arthroscopically, utilizing minimally invasive techniques involving small incisions, a telescope, camera, and specialized instruments. Dr. Niraj Ranjan Srivastava specializes in arthroscopic PCL surgeries due to the numerous benefits it offers, including excellent visualization of knee structures, minimal scarring for improved cosmetic outcomes, reduced tissue damage and bleeding, decreased post-operative pain, early rehabilitation, and shorter hospital stays.

For patients undergoing PCL surgery for suitable indications and diligently following post-operative rehabilitation (typically spanning 6-9 months), there exists a high probability—ranging from 90 to 95%—of achieving favorable outcomes. These individuals typically demonstrate excellent muscle strength, restored knee stability, and a pain-free range of motion. Consequently, they are often able to resume their pre-injury occupations or sports activities with confidence.

The standard procedure for PCL reconstruction involves several precise steps to address the torn ligament and restore stability to the knee joint. Beginning with anesthesia administration, a tourniquet is applied to facilitate a clear surgical field. Diagnostic arthroscopy is then conducted through small incisions to assess knee joint integrity and address any associated injuries. Clearing the remnants of the torn PCL follows, with careful identification of insertion sites for the new ligament. Graft harvesting, either from hamstring tendons or the patellar tendon, is meticulously performed, with measurements taken for precise sizing. Drilling of bone tunnels and insertion of the graft ensue, with fixation devices employed to secure the ligament in place. Thorough arthroscopic assessment verifies the position, tension, and strength of the reconstructed PCL. Wound closure and dressing placement complete the procedure, followed by the application of a supportive knee brace to aid in postoperative recovery and stability.

After your PCL surgery, our team will oversee your recovery process. Typically, hospital stay lasts for 1-2 days. As soon as the anesthesia wears off, patients can begin moving their toes and ankles. Food and water intake can commence 2 to 3 hours post-surgery, alongside suitable pain relief medication administered intravenously or orally. Walking can be initiated on the same or the following day, often with the aid of elbow crutches or a walker for mobility support. The duration of crutch assistance may vary, typically spanning 2 to 6 weeks depending on individual progress. Ice packing, done 3 to 4 times daily, continues for 4 to 6 weeks post-discharge. Patients are permitted full weight bearing with their knee brace locked in extension at 0 degrees for the initial 2 weeks. Subsequently, the brace allows for 90 degrees of knee flexion after 2 weeks, progressing to full flexion as tolerated after 6 weeks. The knee brace is worn for a total of 3 months. During this period, patients are advised to place a pillow under the calf of the operated leg to prevent posterior sagging of the tibia and protect the new ligament, a practice maintained for 3 months. Additionally, they receive guidance on prescribed exercises and are encouraged to continue rehabilitation for 6-9 months under the supervision of our physiotherapist, with weekly monitoring for the initial 3 months. Continued physiotherapy for a minimum of 3 months is recommended to restore normal knee motion, muscle strength, and stability. Compliance with PCL rehabilitation significantly enhances the likelihood of a positive outcome, with restored stability enabling resumption of most normal activities, including sports. Office-based work can typically resume after 2 weeks, provided transportation is arranged. Driving is permissible after 4-6 weeks, followed by motorbike riding after 6-8 weeks, provided the knee demonstrates reasonable pain relief, good range of motion, strength, and stability. Heavy-duty work can be undertaken after 3 months. Sporting activities are generally restricted for the first 6-9 months, during which knee exercises, weight training, and sports-specific training are conducted. Full-intensity sports participation is sanctioned after 9 months of rehabilitation.

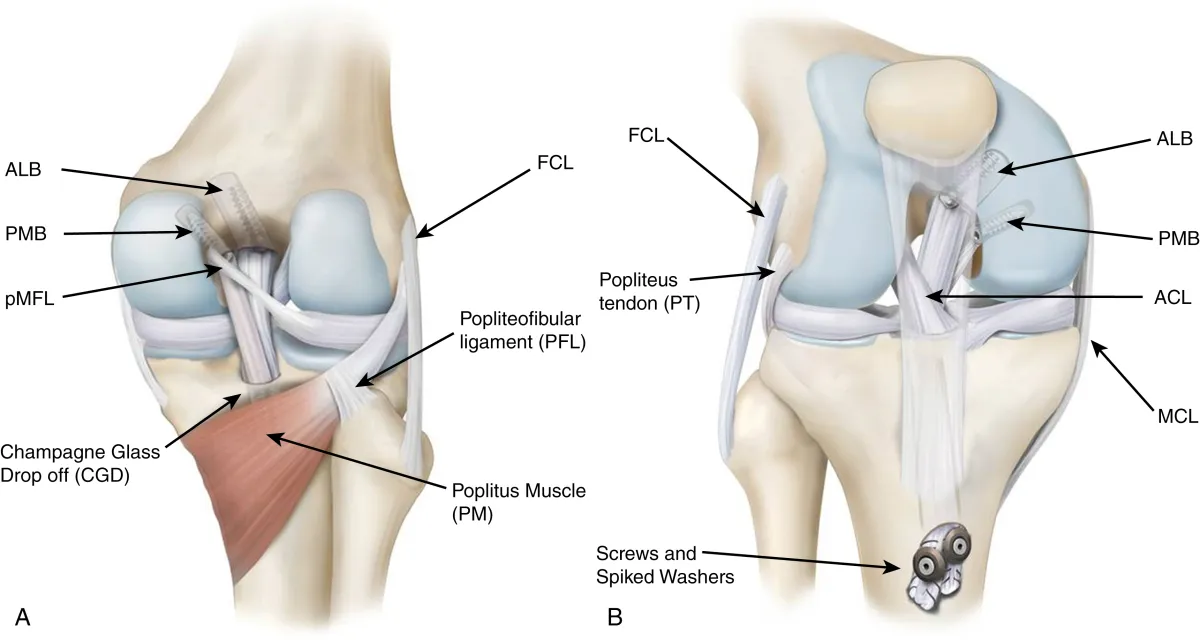

PCL avulsion fractures are managed conservatively or surgically based on factors such as fragment size, displacement, patient age, and activity level. Conservative treatment is typically prescribed for undisplaced fractures, involving immobilization in a PCL knee brace for 3 months. However, serial x-rays are conducted during the initial 4 weeks to monitor fragment stability and healing progress. Gradual knee flexion is introduced with brace support after 4 weeks, alongside the use of a pillow under the calf to prevent posterior tibial sagging. Displaced PCL avulsion fractures may necessitate arthroscopic intervention for small-sized fragments. Specialized sutures are arthroscopically tied around the fragment and brought out anteriorly through drill holes in the upper tibia. Following confirmation of proper fracture reduction via x-ray, the fragment is secured using suture knots over a disc or through additional drill holes. For larger fragments, an open posteromedial approach is utilized to reduce the fragment under direct vision, securing it to the upper tibia with screws and washers. Post-surgery, patients are provided with a PCL knee brace and mobilized non-weight bearing with crutches for the first 4 weeks, transitioning to full weight bearing after 1 month. Knee flexion begins at 2 to 3 weeks post-surgery, contingent upon confirming stable fracture fixation via x-ray. Free knee range of motion within the brace is permitted after 1 month, with brace wear recommended for 3 months. X-rays at 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-surgery are conducted to evaluate fracture healing progress. Subsequent rehabilitation follows a standard PCL reconstruction protocol.

As with any surgical procedure, PCL Reconstruction carries inherent risks that patients should be aware of. These risks include potential complications related to anesthesia, such as allergic reactions to medications and breathing difficulties. General surgical risks, such as bleeding and infection, are also present. Additionally, specific risks associated with PCL Reconstruction include post-operative knee stiffness, failure of the ligament or graft fixation devices, and the possibility of an avulsion fracture failing to heal properly. Patients may also experience knee pain, weakness, or numbness, as well as complications like blood clots, nerve or tendon injuries, and difficulty with kneeling. Furthermore, there is a risk of patellar fracture if a patellar tendon graft is used, and the new ligament may rupture if the knee is reinjured. It's essential for patients to discuss these potential risks with their healthcare provider and carefully weigh them against the anticipated benefits of the surgery.

Athletes with PCL injuries typically resume their sport at their pre-injury level after undergoing appropriate rehabilitation without surgery. For those who opt for surgical reconstruction, most are capable of returning to their previous level of physical activity within one year post-surgery. However, it's important to note that some patients may develop osteoarthritis in the affected knee joint as a long-term complication, although not all do. On average, symptoms of arthritis tend to manifest around 15 to 20 years following the initial PCL injury.

Address

8/92, Sector 8, Ismailganj, Indira Nagar, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh 226016

Monday to Friday

10am - 8pm

Appoinments

+91 - 8840223370